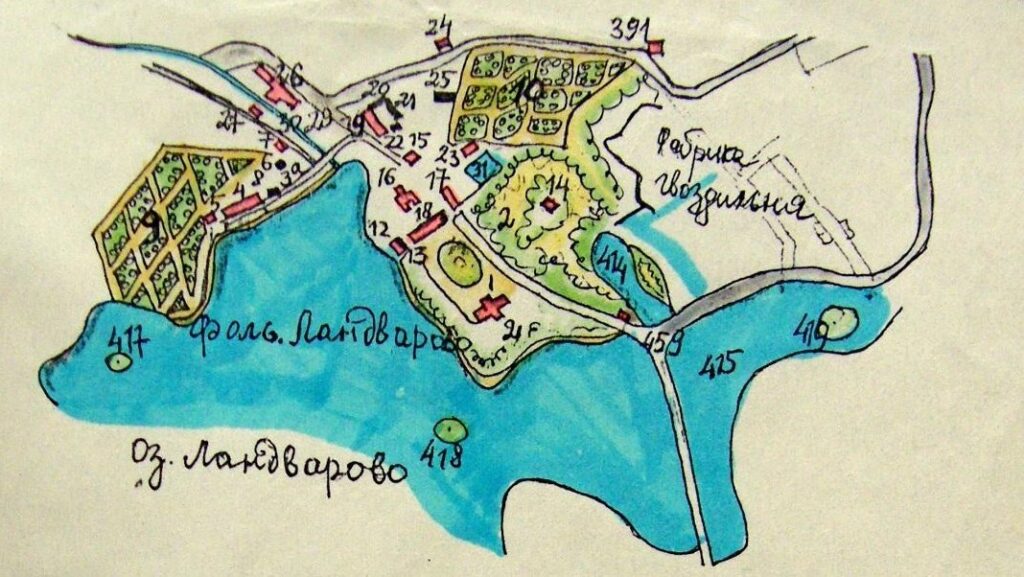

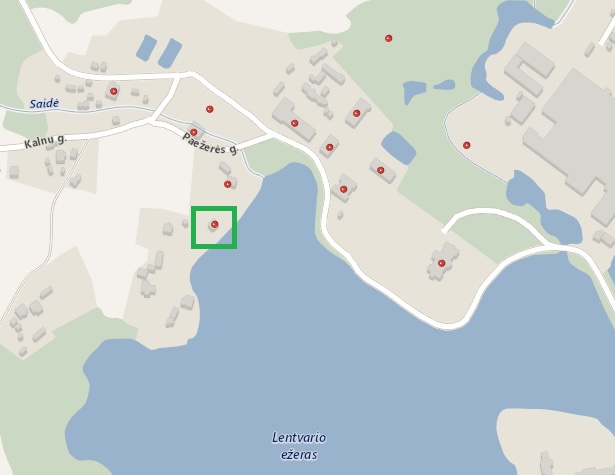

Many tourists who come to Lentvaris Manor first visit the park of the Tyshkevich Manor without even thinking that just across the pond, in the summer, there was a bustling life. At the end of the 19th century, in front of the palace, along the pond, there was a garden, three conservatories (summer, winter and new) and a smokehouse. The buildings were connected by a spacious courtyard, which could be accessed by a road that is now a branch of Paežerio Street.

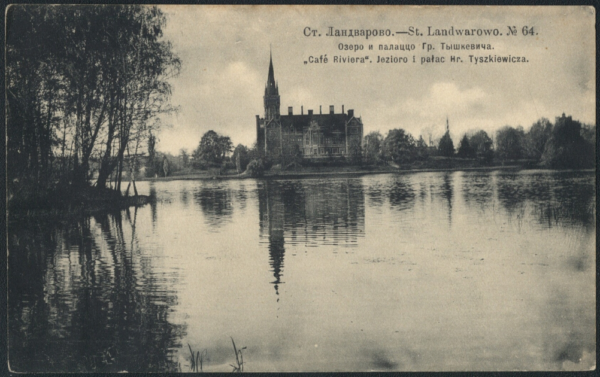

After the completion of the long reconstruction of the palace, around 1900, Counts Vladislovas and Marija Kristina Tyshkevich decided to open a café, the Riviera Café, next to the summer conservatory. The idea was not accidental: many trains passed through Lentvaris, and there was a lot of visitors changing and waiting at the station. There was nowhere to eat in the town, or the eateries did not meet the expectations of wealthier travelers. Later on, the Hilerowicz Hotel and Inn were also established in the town, but it catered to the needs of the less affluent visitors.

The derelict buildings of the Riviera, now standing, no longer resemble the bustle that once took place there, but even these architectural remnants still look impressive. Heritage conservationists found that the red brick-built café building used to have a spacious hall with high ceilings. The facade of the expressive café is decorated with rectangular turrets. Two sculptures of Atlanteans framed the facade of the building. The front of the building once had a forged, ornate hook for hanging a lantern. At night, the outdoor lantern illuminated the cobbled courtyard and showed visitors the way.

The family of Tyshkevich turned to tried and tested new means of advertising to make their new resort famous. The first step was to choose and publicize the name of the café. In the language of the upper classes at the time, “riviera” meant the kind of relaxation that could be enjoyed on the coasts of Italy or France. In the imagination of the owners, Lentvaris has a lakeshore, and with the establishment of the café and the creation of a new garden, and the opening of a tropical conservatory, it was as if the café was reminiscent of those Mediterranean shores. It was a good idea, all that was needed was to set up the café properly and to advertise the whole complex.

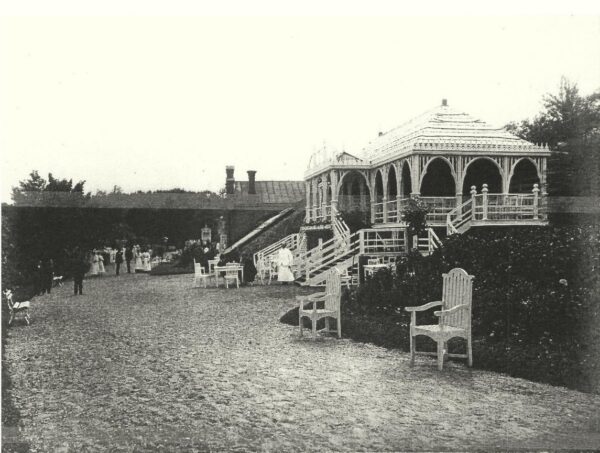

Photographs of the café’s exterior at the time show that the space had been extended. Single-story extensions surrounded the Riviera on both sides. It is likely that the annexes housed the kitchen for the staff. The café’s functional space was extended by a spacious wooden terrace. Chairs were brought outside in case of an influx of guests or to watch a performance. The café was, therefore a place to enjoy the outdoors in the summertime and to move inside when the weather cooled.

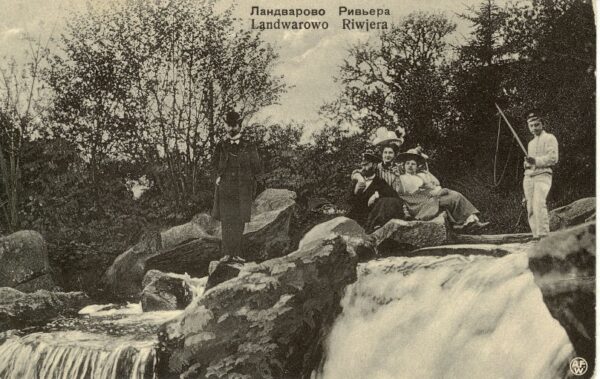

Those who like to go for walks could use the park next to the café. A chapel with wooden benches was set up in a pine tree for those who wanted to sit outdoors. Lentvaris was developing into a suburban resort of Vilnius, and the Riviera itself took on the appearance of an entertainment complex. The private and commercial areas of the estate were separated, leaving the palace environment to the owners and the amenities of Riviera to the guests.

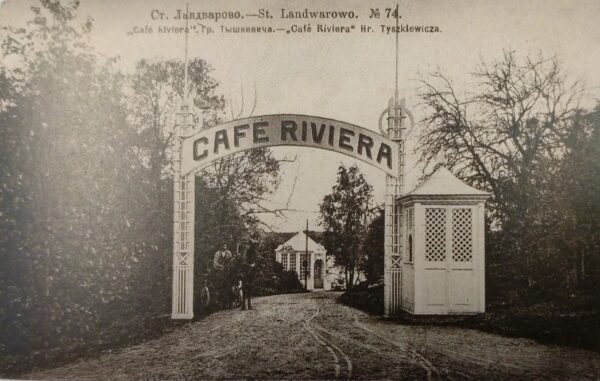

The Riviera could be accessed by land. Visitors to the café were picked up at the train station by coaches. As soon as they pulled up to the café, they were greeted by a gate with a large sign reading ‘CAFÉ RIVIERA’. The caretaker’s hut, visible on the postcards, would indicate that there was a charge and that order was maintained. In those days, estate parks were not open to passers-by; there had to be a specific purpose.

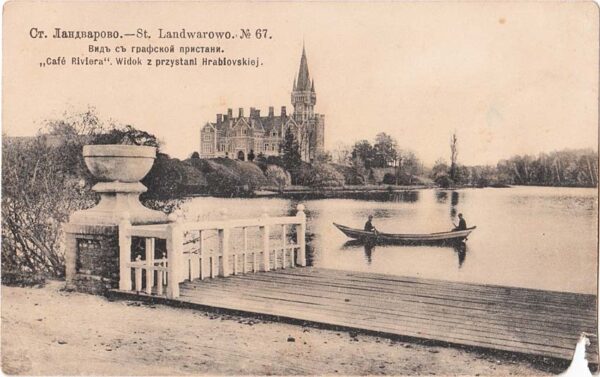

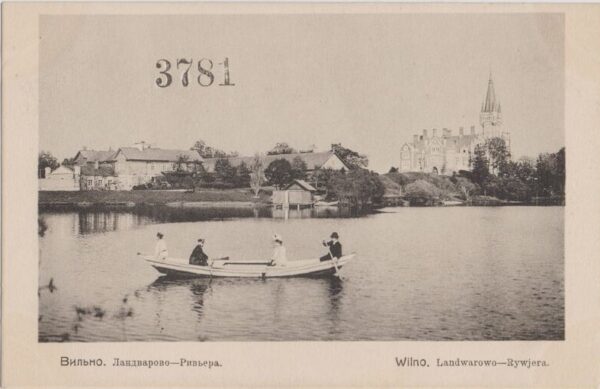

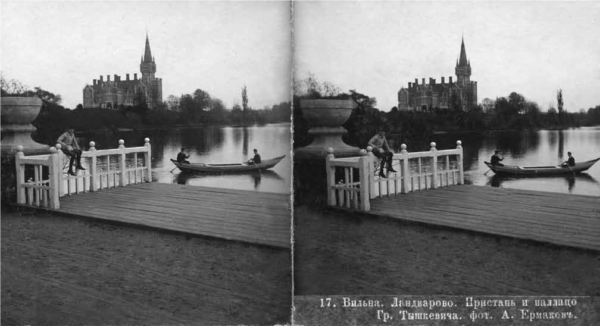

There was also a pier next to the café. Guests who wanted to enjoy the water could take a boat on the lake. On more than one occasion, photographs have been taken of guests enjoying such boating. The corners of the café’s pier are decorated with two huge flower pots. The edges of the pier are fenced off for security reasons.

The plan for the advertising campaign had to take into account those measures that were effective and could highlight the services offered. The main advertising tools of the time were periodicals and postcards. Advertising in the press format part of the advertising company, but it is not possible to say at present, without looking at the extensive Russian and Polish periodicals, to what extent the Tyshkevich family was concerned with this.

All that is known is that commercial information on the sale of flowers, fruit trees, and other goods from the estate farm was published in the Warsaw magazines Ogrodnik polski (1902, no. 21; 1903, no. 19) and Dobra Gospodyni (1904, no. 3). The unattributed press cuttings preserved in the Vrublevskis Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences testify that the Riviera’s surroundings were repeatedly featured in the pages of the Polish press.

The postcard was the main means of interpersonal communication at the time. It was not difficult to get into postcards and spread the idea of your resort: postcard publishers of the time were looking for new objects, ideas, and business opportunities. Postcards featuring images of Lentvaris were published in the early 20th century by publishers in St Petersburg, Moscow, and Vilnius: Ambraam Fialko, Davydas Vizūnas, Bolesław Stadzevičius, Antoni Žukowski and Władisław Borkowski, the Society of the Red Cross of St Eugenia, the Press Contractor, the Suvorin Contractor, and Petras Vileišis. Most of these publishers chose more neutral names for Lentwari, without creating a clear image of the resort. Apparently, in most cases, the publishers did not receive such a special request from the counts.

From around 1907 onwards, the image of Lentvar as a riviera appeared in the publications of the well-known Vilnius publisher A. Fialko (1 postcard), the St. Eugenia Red Cross Society in St. Petersburg (1 postcard), and the company “Press Contractor” (4 postcards). It is very important that this image was consistently disseminated by the Moscow-based press company “Press Contractor”. The company had the exclusive right to distribute the postcards it issued on the Russian railway network. Passengers who bought these postcards at various stations in the Russian Empire could naturally become interested in the new resort near Vilnius. The Tyshkevich family themselves and the guests of the café were probably able to buy postcards of Lentvaris on the spot.

The letters reached relatives, acquaintances and business partners, and so word of the new resort spread. It is important to note that there must have been an agreement between the Tiškevičius, Fialko, and the Press Contractor, because all the postcards from Lentvaris, even those that did not depict the Riviera Café and the attractions it offered, were marked with the Riviera name. The display of images of the enclosed park was not fair, but the interesting images acted as a powerful advertising tool. Later, probably after the break in the relations of “Press Contractor” with the Tiškevičius, the same images of the manor by A. Jermakov were published by the company’s successor, A. Suvorin & Co., from 1910 onwards, without the Riviera designation.

The Moscow photographer A. Jermakov, who visited Lentvaris in 1907 on behalf of the “Press Contractor”, also benefited from the additional benefits. The working group ‘Science and Education News’ published a collection of stereoscopic images by this photographer, which included photographs of Vilnius, Naujoji Vilnia, and Lentvaris. Stereoscopic photographic technology made it possible to create three-dimensional images by observing the photograph through special glasses. Lentvaris’s inclusion in the then-growing photographic entertainment was significant in the perceived efforts to promote this newly-born resort.

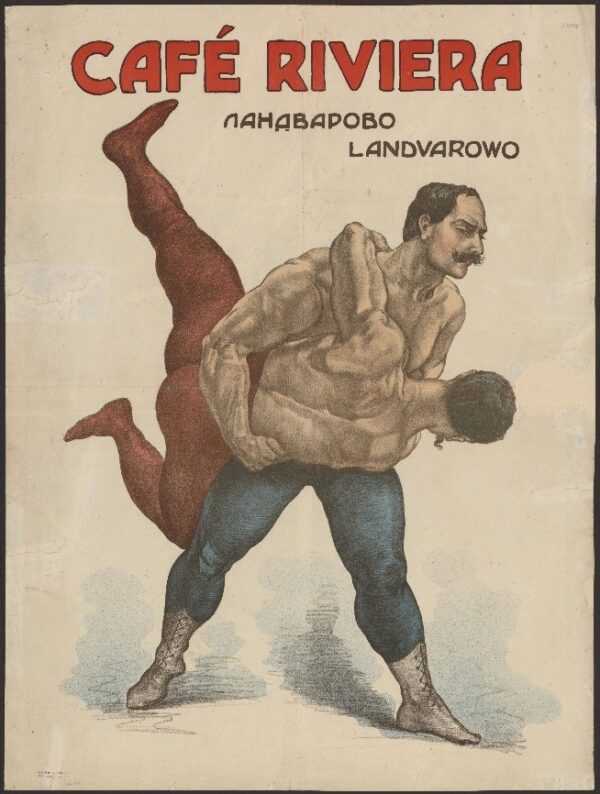

Count V. Tyshkevich sought to attract visitors to the Riviera with various events. Concerts by a Neapolitan ensemble, visiting theatre companies, illuminated boats on the lake, even a floating theatre stage on the lake, and amateur bicycle races formed the backdrop to the entertaining life. A surviving poster advertising the café bears witness to Tyshkevich’s determination to impress the visiting holidaymakers.

Until 1913, Lithuania had no color printing equipment, so it was no coincidence that the Count turned to the chromolithography of R. Golikė and A. Vilborg in St Petersburg. There were probably not that many advertising posters in the whole of Russia advertising the café in such a witty way. In Lithuania, posters were usually issued for art and farm exhibitions. These are one-day prints, but this one does not resemble one. The existence of posters advertising Lithuanian commercial enterprises has hitherto been unknown.

The owner of Lentvaris, V. Tiškevičius, although of a peaceful disposition, is depicted in this poster as overcoming himself in a French wrestling style. This style began to gain popularity in Lithuania around 1907, so the chosen storyline was also quite interesting and eye-catching. The dominant red color in the advertisement adds to the shocking impression of the fight.

The café was not a ring, and there was no wrestling or serious fights among the guests; it was a place of relaxation for cultured people, so many viewers must have asked themselves, what is Vladislav trying to say? It was to subtly say: ‘You do not yet know what awaits you at the Tiškevičius’ café Riviera. The owner will try to surprise you, even if he has to outdo himself.”

Despite the efforts of the Tyshkevich family to publicize the Riviera entertainment complex, the First World War and the disasters that followed completely changed the history of Lentvaris. Lentvaris did not become the new Riviera, and the café buildings are slowly falling into disrepair without having acquired new uses.

Sources and Literature:

- Cultural Heritage Register. Available online: https://kvr.kpd.lt/

- L. Balėnaitė. “Lentvaris Manor: Historical Studies.” Vilnius County Archives, f. 1019, inv. 11, file 3253.

- Materials on Lentvaris Manor collected by Ž. Krūminytė. Archive of the Vilnius Territorial Division of the Cultural Heritage Department.

- “Postcards of Vilnius Views 1897–1915.” Compiled by Dalia Keršytė. Vilnius: Lithuanian National Museum, 2019, pp. 203, 255, 361, 364, 384, 390, 422, 440, 468, 488, 489, 498, 515, 519, 566, and others.

- Dainius Junevičius. Research and Dissemination Project of Spatial Photographs of Lithuania Preserved in Museums and Private Collections. “Lithuanian Museum Collections,” 2017, no. 16, pp. 13–16.

- Giedrė Petreikienė. Café “Rivjera” – An Oasis of Entertainment in the Resort Town of Lentvaris [online resource]. “Klevų alėja,” February 28, 2019.